THE FRAUD WE CALL RECRUITMENT

HOW GHANA IS FAILING ITS YOUTH

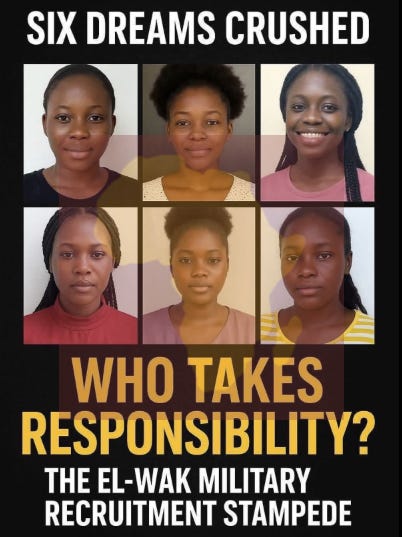

It is unfortunate, disheartening, and heartbreaking—the stampede incident that occurred at the Elwak Sports Stadium during the GAF recruitment exercise that claimed the lives of six applicants and injured many others. Are there lessons we can learn from this? Are there reforms we can make as a country?

Let me tell you a story of mine in 2016. I was a young man with good credentials—a bachelor’s degree from the University of Ghana and a master’s degree as well. Yet, despite all these qualifications and years of effort in developing myself, I was never gainfully employed in my own country. In fact, I didn’t get full-time employment in Ghana until after I traveled abroad. No wonder almost every young person wants to leave the country.

In 2016, I got myself affiliated with politics, hoping it would help me secure a job. One day, some party leaders called me and told me that the constituency executives had recognized my efforts during the campaign and were going to help me get a job. At that time, anything would do for me. As a young man in my late 30s with a graduate degree but unemployed, living with my parents was both frustrating and embarrassing. The job they recommended was at the airport as a security officer.

My friend and I, who were both affiliated with the party, were invited to the Elwak Stadium for screening. As part of the process, we went through fitness tests and some physical exercises. The funny part—which my friend and I still laugh about today—was when we were asked to strip naked so that our testicles could be inspected to confirm that we had two. We laugh over this everyday. Anyway, that is too much information already.

Fast forward about a month later—we still hadn’t heard anything about whether we had been selected. I thought this was a party protocol arrangement. When we reached out to our contacts, we were told to forget about it because the positions had already been given out long before we even attended the screening. They assured us that if another opportunity came, they would prioritize us.

Let me tell you another story.

A year later, a position was announced for a National School Health Educational Coordinator under the Ministry of Education. This role became crucial after the Influenza H1N1 outbreak at Kumasi Academy Senior High School, which killed 17 students in 2017. I applied for the role with my Master of Public Health qualification and was selected for the aptitude test. I passed that and was later invited for an in-person interview.

During the interview, I noticed the interviewers’ curiosity about my background, and how deeply they probed to understand my ideas for this new role. It was a great interview, and I left confident.

As I was walking back through the Ministries area afterward, a young man around my age approached me politely. He told me he was a national service person working in the ministry. After learning we were both old Vandals from the University of Ghana, he told me something I will never forget.

“V-mate,” he said, for which I quickly responded “Sharp” . “I was in the interview room taking notes for the panel. I can tell you for a fact—you are the ideal candidate for this role. You scored the highest in the aptitude test. You wrote the best report. Others wrote essays like SHS teachers, but yours was the only proper report, and that is exactly what they were looking for.”

“But,” he continued, “the sad truth is that the person selected for this role has already been chosen. The order came from above. Everything happening here is just a formality—for bonuses and sitting allowances. I hope you get it, but don’t hope too high.”

We exchanged contacts, and he is still my friend to this day.

These experiences, and many others before and after, taught me important lessons about public sector employment in Ghana:

You do not get a job based on merit.

Corruption is real—you must pay to get in.

You must know someone (or be known by someone) to get in—and even then, you still pay.

The real selected applicants rarely attend interviews; when they do, it’s just for formality.

But is this how things ought to be? Can’t we as Ghanaians do better for ourselves, at least for once?

For goodness’ sake, the National Security Agencies—especially the Armed Forces—are among the most important institutions in our country. That is why the President, the highest authority in Ghana, is called the Commander-in-Chief of the Ghana Armed Forces. National security is crucial; we cannot afford to get it wrong.

So who is to blame? Leadership?

Yes, to some extent. We cannot all be at the helm of affairs. That is why we elect leaders—to represent our interests and work for the common good of Ghana. But before we blame leaders, let us look at ourselves. Leadership is always a reflection of the people, and vice versa.

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.”

Bad things happen because so-called good people refuse to speak up. Corruption persists because we tolerate it. When we fail to speak, bad precedents become acceptable norms.

The recruitment process for Ghana’s security services is fraudulent, exploitative, and corrupt. In my view, what is happening with security services recruitment should never be legal. The government is using the unemployment crisis—a crisis they themselves contributed to—to exploit and extort the same poor citizens they should be helping. Why on earth should people pay money for before they get employed.

Now let’s talk about employment and global recruitment standards.

Across the world an din many countries, there are laws guiding recruitment processes to ensure they are legal and ethical. Yet, in Ghana, even at the highest levels of leadership, we have lost our sense of ethics in this process. And if the highest authorities lack ethics, how can the institutions under them do better?

Global labor standards on recruitment fees are clear:

Employers—not applicants—must pay recruitment costs.

Charging jobseekers creates conflicts of interest and enables fraud.

Many countries have laws that prohibit employers or agencies from collecting any form of recruitment fee from applicants.

It is common sense. An employer needs workers to generate profit, and employees receive only a fraction of that profit. If the business is not profitable because employees underperform, they are laid off. So why should an employer charge someone for a chance to work?

Yet this is exactly what is happening in our security services. People are made to pay money—through the sale of application forms—for a 0%–3% chance of being selected. This is pathetic and a bad precedent.

And let’s consider the nature of the job. These are positions of service—roles where people are literally putting their lives on the line for their country. The job is risky. It should be a role of honor, yet the government expects applicants to pay for the chance to die in service to the nation. It just doesn’t make sense.

Worse still, the government knows that most applicants are applying out of desperation, not passion. The economic struggles force many to take any job available, even one they are not truly inclined to do. And because of that desperation, they charge them recruitment fees. This is daylight exploitation.

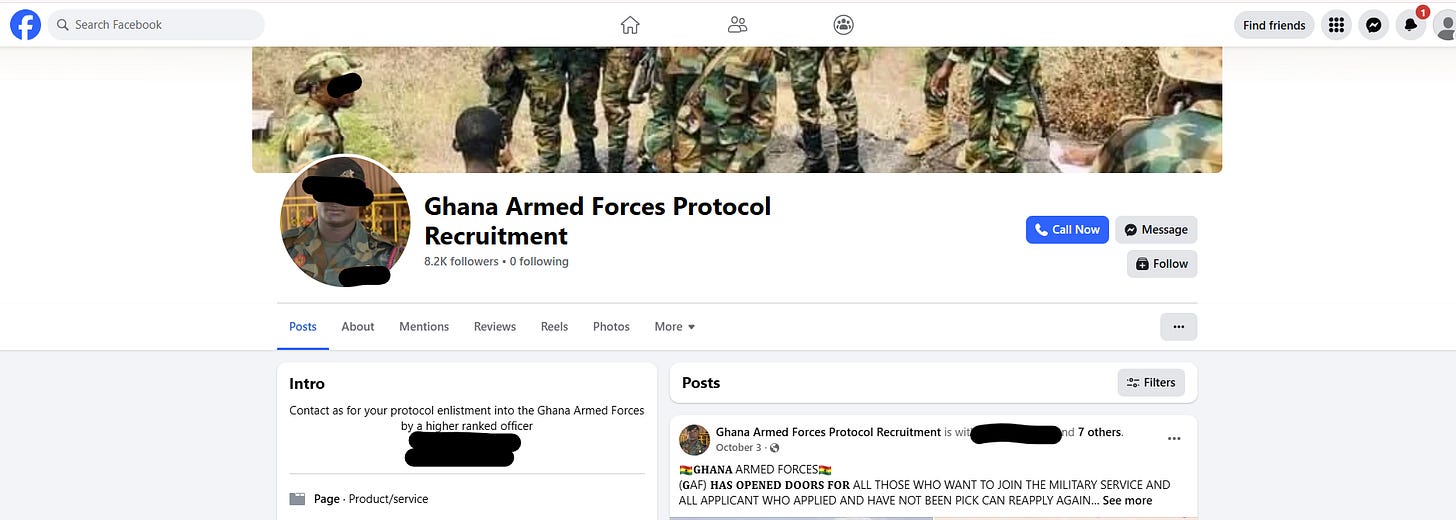

Last year, it was reported that 90,000 applicants applied for the Armed Forces recruitment, with only 3,000 selected. This year, 60,000 applied, and only 4,000 were to be picked. If these numbers are accurate, then the GAF made between GHC 12–18 million from selling application forms alone. And they do this knowing perfectly well that the majority of applicants will not be selected—not because of merit, but because the slots have already been allocated through bribery, political protocol, military protocol, and favoritism. I once chanced on this page on facebook and I said to myself, wow. It is really a business.

You may deny this, but anyone living in Ghana knows it is true. And this problem is not limited to the current government—it has existed under previous governments as well, and will continue if nothing is done.

Ask any officer currently serving in the security agencies how they got in. Nine out of ten will tell you it was through protocol or bribery. I personally experienced this when I attempted to help my brother join the Immigration Service. I was told to pay GHC 50,000. How can someone who has GHC 50,000 be desperately looking for a job? I later learned that those who don’t have upfront cash are enlisted, and the money is deducted from their salaries for 6–12 months until the bribe is paid off.

I am not saying these things to shame my country. I am saying them because I care. Even though I may never join the military now because I am gainfully employed, someone must speak for the voiceless. Evil thrives because good men keep quiet.

Some will defend the recruitment fees by claiming they cover administrative costs—processing applications, shortlisting, online portals, verification, security checks, etc. These excuses are weak and expose the incompetence of the public sector in managing simple recruitment systems in a technologically advanced world.

Takeaways

I hope this article will push for reforms and bring some decency into government recruitment:

The youth must be angry enough to demand transparency and refuse exploitation. Silence is acceptance. Speak up.

Abolish application fees for government jobs. Government recruitment laws should eliminate application fees—90% of applicants are going to get rejected anyway.

Stop sharing recruitment slots among MPs, Ministers, Chiefs, and Political figures. Recruitment should be national, not partisan.

Recruitment must be merit-based, not favoritism-based. Let the best candidates serve Ghana.

Criminalize recruitment bribery and protocol systems. These crimes should be made felonies, with strict long-term penalties including jail terms.

Ghana is bleeding and it’s our silence that is killing her. Every year, thousands of Ghanaian youth wake up early, queue under the hot sun, and pray for a chance to serve their country. They run. They sweat. They faint. Some collapse. Some die.

And after all that, the job is already gone—to someone who paid, someone connected, someone with protocol. How long will we accept this? Ghana is not poor. Ghana is not cursed. Ghana is simply mismanaged. And until we fight corruption—not with slogans, but with consequences—stories like mine will remain ordinary, and tragedies like Elwak stampede will continue. The time for truth is now. The time for reform is now. The time to fix Ghana is now.