The Scam of Western Education in Africa

Africa leaders must transform education from colonial-driven theory based schooling to indigenous-driven practical that drives innovation and productivity.

In 1930, the American psychologist John B. Watson argued that the environment largely determines who we become. One of his most frequently quoted statements captures this idea clearly:

“Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in, and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief, and yes, even beggar-man and thief—regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors.”

This statement is simple yet powerful, and it remains as true today as it was then. With the right training methods, rewards, punishments, and social conditions, a person can be shaped into almost anything—including a criminal.

Training is always designed to produce a specific purpose and outcome. What people learn depends largely on what the teacher, the system, or the institution intends them to become. A curriculum is never accidental; it is carefully structured to transmit certain skills, values, and limitations. The depth of learning, therefore, is determined not only by the learner’s ability, but by how far the system intends to empower them.

This raises an uncomfortable but necessary question for Africa: what exactly are Africans trained to become?

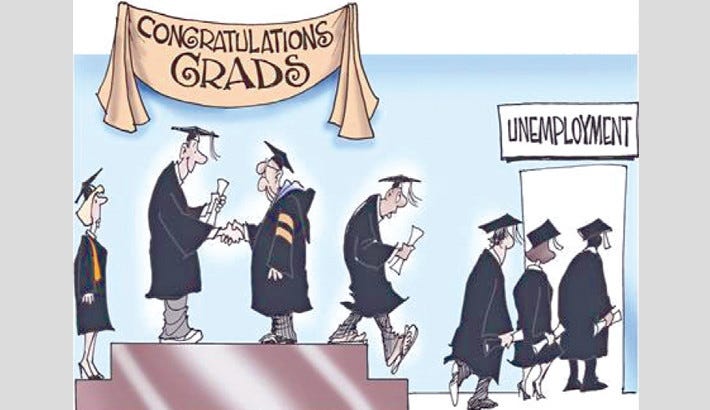

Most African countries produce thousands of graduates every year across all academic fields. Yet, despite having numerous engineering degree holders, we have not built machinery, vehicles, or technological systems of our own. In healthcare, we rely almost entirely on imported medical equipment, pharmaceuticals, and instruments. Many business graduates roam the streets unemployed, unable to start businesses or build industries. African scientists, though highly credentialed, rarely produce the tools their professions depend on. In the social and political sciences, we continue to experience failed political systems and persistent economic hardship.

This pattern repeats across nearly every field of education. The question, therefore, becomes unavoidable: are we truly being educated, or are we simply passing time under the illusion of education?

Were You Schooled or Educated? Know the Difference

Many Africans believe they are educated. In reality, most of us have been schooled, not educated. These two are not the same.

Schooling is the formal, institutional, and organized process through which a society trains, disciplines, and socializes individuals—especially children—according to its values, economic needs, and power structures. It operates through standardized curricula, teachers, examinations, rules, and certificates. At its core, schooling is designed to transmit approved knowledge—what those in authority decide you should know. It shapes behavior and obedience through time discipline, hierarchy, and compliance with rules.

In this sense, schooling becomes a structured method by which society conditions individuals to become particular kinds of workers, citizens, and subjects—sometimes for collective good, but often for control.

Education, however, operates at a higher and more transformative level. It is not primarily concerned with fitting individuals into existing systems, but with developing the capacity to think critically, question assumptions, and understand the world deeply enough to change it. An educated person—or an educated society—is one that possesses the intellectual tools to shape its own future rather than inherit one imposed upon it.

Schooling trains a person to become whatever the trainer desires. Education equips individuals to think independently, create, solve problems, and reproduce value. We often confuse the two. So ask yourself: with all the years you have spent in school, were you schooled—or were you educated?

The Purpose of Western Education to Africans

Africa adopted a western education system designed and imposed by colonial powers - with the sole purpose to control and influence the thought processes of the people. It is naïve to believe that the same colonial masters we fought to free ourselves from would provide an education that would allow us to compete with them or surpass them. That was never the intention.

Colonial education in Africa was designed primarily to produce literate clerks and intermediaries—not innovators or industrial competitors. Africans were trained to read, write, and speak the colonial language well enough to serve administrative functions and facilitate colonial control, not to build independent industries or technologies.

This explains why many African graduates can write excellent English, Arabic, Portuguese or French, memorize textbooks, and pass examinations, yet lack practical, employable, or productive skills. The system was never meant to make us self-reliant. It was designed to make us functionally useful while remaining dependent and compliant. Yet we mistake literacy and mastery of scripted curricula for education.

If the goal had been genuine empowerment and transformation, our education would have equipped us to build planes, cars, medical equipment, agricultural machinery, household appliances, and advanced technologies using the abundant resources we possess. But such competence would make Africa self-sufficient—and therefore unprofitable to exploit.

Another core objective of this system is compliance. Africa’s education model largely follows what is popularly called the “chew and pour” system in Ghana—memorize content, reproduce it in examinations, and move on. From kindergarten to university, success is measured by recall rather than creativity, innovation, or problem-solving.

Have you ever wondered why, as a people, we seem to enjoy being told what to do by colonial powers rather than developing solutions to our own problems? From kindergarten to college, our educational system follows a method where students are given content to memorize and reproduce. The “best” student is the one who recalls the most information, not the one who thinks the deepest. If students were trained by being presented with real problems and required to search for solutions, they would learn how to learn, how to think independently, how to question assumptions, and how to become innovative and self-reliant. But that is not what we do. Instead, we train people how to consume fish fed to them rather than taught how to fish. As a result, we are conditioned to wait for direction—waiting to consume goods from foreign nations, waiting for outsiders to tell us how our economy is performing, waiting for them to certify our elections, advise us on how to manage our resources, and validate our decisions. This system of training has programmed our mindset to wait to be told what to think and do, instead of deciding and doing what is best for ourselves.

The outcome is predictable. Students trained under this system rarely challenge assumptions or question relevance. They accept what they are taught as unquestionable truth. Because Africans have been schooled to believe what colonial systems wanted them to believe, many accept inherited political and economic structures without question—even when those systems repeatedly fail. Does it surprise you that many so-called educated Africans carry colonized mindsets—seeing everything African as inferior, aspiring to Western lifestyles and culture, and believing that Africa cannot develop without colonial powers ?

Those who manage to rise beyond schooling into true education—those who challenge the status quo and provoke independent thinking—are often silenced, marginalized, or eliminated. History reminds us of this through figures such as Dr. Kwame Nkrumah and other Pan-African visionaries.

The Deception of Western Education

Every successful scam follows a pattern: the victim is made to constantly believe they are winning, even as they are losing. Anyone who has been scammed will tell you that the illusion of progress always comes before the collapse.

Western education, as imposed on Africa, operates in a similar way. It offers entitlements—degrees, certificates, and diplomas—that create a sense of superiority and achievement. Yet beneath these titles lies an uncomfortable truth: many highly credentialed individuals cannot produce anything of tangible value.

Once people are convinced they are highly educated, they become emotionally invested in protecting that identity. Questioning the system then feels like a personal attack, making reform even more difficult.

Consider this example. Ghana has many professors and PhD holders in engineering, yet little innovation to show for it. Meanwhile, innovators like Apostle Kwadwo Safo Kantanka—often dismissed as “uneducated” because he lacks Western academic credentials—have designed and built cars, helicopters, televisions, and automated systems using sensors, in some cases ahead of mainstream adoption. Ironically, many of the highly schooled but unproductive elites are unwilling to humble themselves to learn from such innovators.

This raises a disturbing question: who is truly educated—the one with the titles, or the one who can think, create, and build?

Let me be clear: I do not oppose schooling. Literacy is essential, and every African should be able to read, write, and comprehend. However, Africa must reclaim control of its educational system and refocus it on transformative learning—learning that sharpens critical thinking, challenges assumptions, encourages creativity and innovation, and ultimately makes Africa self-reliant and capable of solving its own problems. Leadership must note that, they youth are realizing the hopelessness of our educational system from experiences of frustrated graduates. If national level effort is not reached to make things better, no one will be found in our educational institutions anymore. The people cannot be unconsciously scammed forever.