Cadets Are Ready, Ghana Is Sleeping

A Call for Serious and Strategic Military Recruitment Reform

I love talking about national security issues because they form the backbone of every developed country. Security is the foundation of national development. Tell me a great and powerful nation with a weak army—there is none. Think of the United States, Russia, China, North Korea, Germany, England—each built on strong national security. Strength goes beyond money or wealth; it is the ability to protect people, resources, and the future of generations. That is true wisdom.

Because of this, national security agencies must be extremely intentional about who they recruit into the armed forces. The job requires people who are willing, intrinsically motivated, disciplined, and guided by a deep sense of patriotism. It is not a career for just anyone.

My migration to the United States opened my eyes to how differently countries operate, and why the results vary so drastically. I often compare their systems to those in Ghana, and the contrast in outcomes proves why some nations prosper while others stagnate.

Cadet Talent in Ghana — An Untapped Goldmine

Cadets at High School Level - An Early Training

The video above shows performance of Obiri Yeboah Senior High School Immigration Cadets. This school has won numerous cadet competitions across the Central Region and the entire nation. Their excellence is no accident—they are trained by expert immigration officers, benefiting from proximity to Ghana’s only immigration training school in Assin Foso.

These students are talented, disciplined, and have already been well groomed as future officers of the Ghana Immigration Service. They may not know everything yet, but compared to someone with zero prior training, they possess a solid foundation — marching, saluting, defense basics, discipline, and basic service terminologies.

Obiri Yeboah Senior High School is not an isolated case. Almost every high school in Ghana has a cadet corps trained by skilled instructors as well. In high school, these students receive no financial reward, no academic bonuses, no incentives for their participation in cadet programs — just a certificate. So why do they join? In my own view, their participation is fueled by intrinsic motivation, passion and love for service.

They choose to do something difficult, in addition to heavy academic workloads, for no reward but commitment and the passion to be a cadet student. And that alone speaks volumes. We cannot all be cadets, and that is fine, because not everyone has the passion or ability for it.

Cadets at the Tertiary Level — Even More Prepared

At the University of Ghana’s Commonwealth Hall, I had friends in the Vandal Army Cadet Corps. These were intelligent students studying psychology, mathematics, engineering, nursing, and other fields — trained by Ghana Armed Forces personnel. They had both brains and discipline.

Like the Vandal Army, other halls in Ghana universities — Akuafo, Mensah Sarbah, Casford, Katanga, Continental — also have well-trained cadet corps. The story is the same across universities, polytechnics, nursing colleges, and teacher training institutions.

Before I proceed to make my national policy recommendation for national security recruitment , let us learn from other nations.

What Other Countries Are Doing

To be good at something, learn from the best. Let us examine how stronger nations recruit and train their forces. I will examine the case of the US, Russia and China.

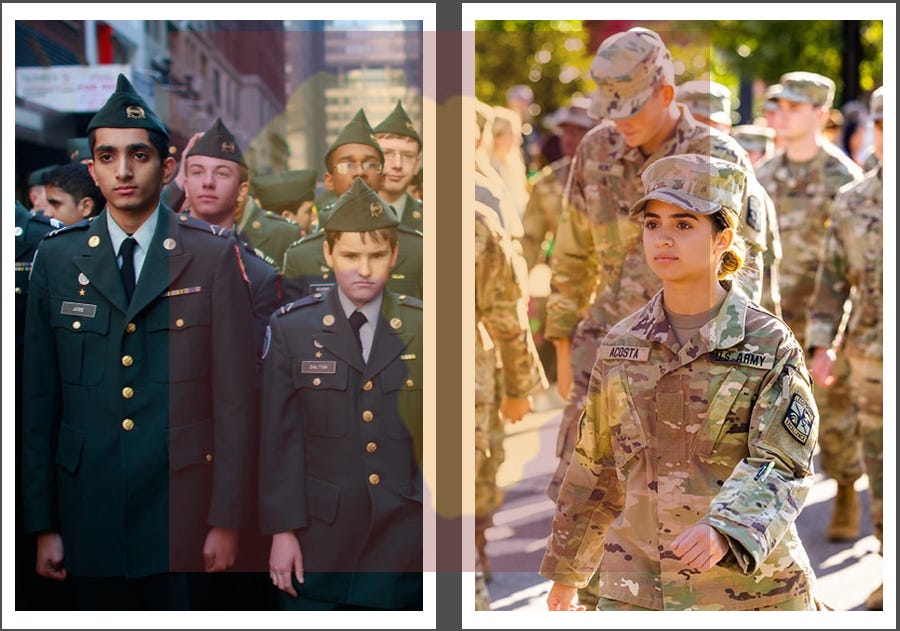

United States — JROTC and ROTC

The U.S. uses the ROTC (Reserve Officers’ Training Corps) and JROTC (Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps) programs as their first line of Security Agency recruitment. ROTC IS a college-based program that trains students to become commissioned officers in the U.S. Armed Forces after graduation. The high school equivalent is JROTC. It is offered at over 1,700 colleges and universities and includes military training alongside academic studies, often with scholarships available to help cover tuition and other expenses. Students in the program can earn scholarships, develop leadership skills, and graduate ready to serve as second lieutenants in the Army, Navy, or Air Force. Students take part in military science classes, physical training, and summer training programs, building leadership and teamwork skills that are valuable in both civilian and military life.

I studied alongside ROTC students—they were regular students majoring in engineering, computer science, nursing, and more, while also receiving military training. Their system resembles Ghana’s cadets—but with the crucial difference that the U.S. actually invests in and recruits from theirs.

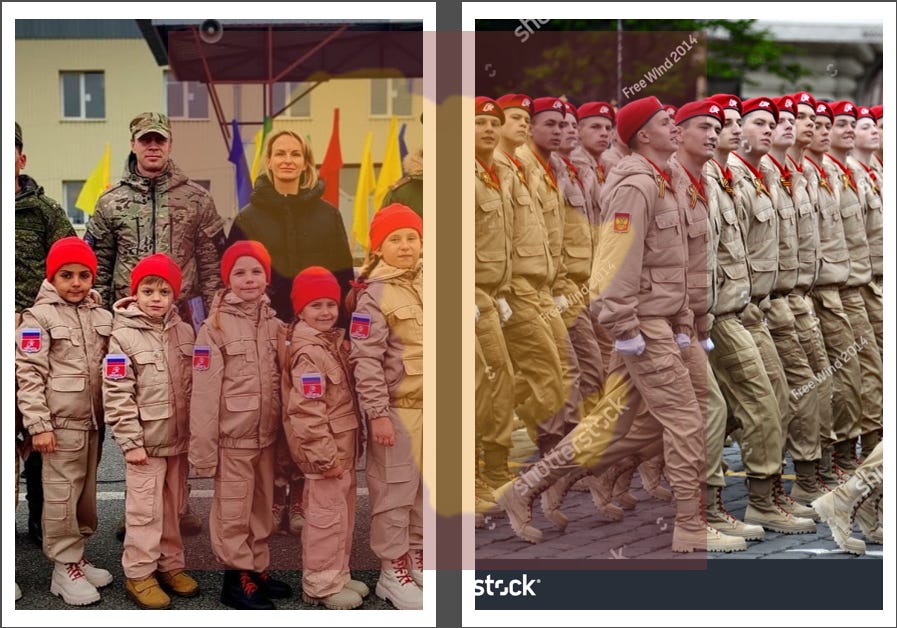

Russia — Yunarmiya and Military Academies

Russia has programs similar to ROTC/JROTC, but they are organized differently and are more closely tied to state-run youth and military-patriotic organizations rather than universities. The largest and most visible youth military-patriotic program in Russia is called Yunarmiya (Young Army).Yunarmiya focuses on military-style training - discipline, marching, drill, physical fitness, survival, patriotism, national defense skills, weapon familiarization and competitions.

Also there are dedicated military universities, such as Combined Arms Academy, Military Technical University, Naval Academies and Air Force Academies.

China — Junxun & University Defense Programs

In China, all high school and university students undergo a short period of mandatory military training called Junxun. They train in Marching and drill, Basic military discipline, Physical conditioning, Intro to national defense and Sometimes basic weapons instruction (non-live fire).

Like the USA, China runs University National Defense Students(similar to ROTC). Like ROTC, students in China attend a regular civilian university and participate in the military program. After graduation Graduates are commissioned as army officers and serve a mandatory number of years in active duty. Like Russia and America, China also has Military Academies.

The Benefits These Countries Enjoy

The benefits of these programs to these countries are that they get a steady, predictable pipeline of new trained lieutenants and officers from diverse academic backgrounds.

This produces officers who understand both military and civilian worlds, are better prepared for the service and bring innovation to the service.

By the time they commission, they’ve had at least 4 years of progressive leadership practice, not just boot camp or short officer school. These programs offer a stabilizing force for recruitment and readiness

These nations invest early because they understand a simple truth: Strong armies are built from young, disciplined recruits—not desperate jobseekers.

So you see, great military nations use similar approaches — training and identifying future military personnel early. Meanwhile in Ghana, even though we have similar systems in our schools and universities, we do not leverage them.

So why are we ignoring this pool of ready, motivated, partially trained, high-potential candidates? The hard truth are these:

Ghana’s leaders are more committed to partisan politics than to national strength and this is killing the recruitment process. When political parties come to power, they recruit their party faithful and loyalists into the security services. They do this so they can have loyal men in uniform to fight for them during elections.

Also, security recruitment has become a cash cow. It is a great source of personal income for people of power and influence. Protocols are sold. Slots are traded. Chiefs, politicians, and powerful individuals use recruitment as a means of reward and enrichment. It becomes a business — not a national service.

But should we entrust the safety of over 30 million Ghanaians to people who were not recruited on merit? You may think this is a small problem, but wait until a crisis or war breaks out — and these individuals cannot deliver.

Furthermore, if leaders of our Armed Forces cannot manage and coordinate mere recruitment processes, how can they manage and coordinate warfare and security of the nation?

THE CALL TO RECRUIT FROM HIGH SCHOOLS AND COLLEGES

Let me be clear: I believe every person can be trained. But it is wiser to recruit the best, the strongest, the most motivated, the most prepared — especially when they already exist in our cadet systems.

I once asked my friend why they joined the cadets at college. Their responses remain the same : they have had the passion since high school and they really enjoy being part of the cadet.

But they also feared one thing—that when the time came to join the army, they might be denied because “in Ghana, it’s all about who you know”. This is heartbreaking.

These are the very people who should be first in line: highly educated, physically capable, motivated, and already partially trained. Yet they fear being pushed aside by protocol, politics, or favoritism.

I am calling for the Ghana Armed Forces, Immigration Service, Fire Service, Police Service, and other agencies to prioritize recruitment from high schools and universities for these reasons:

1. They have the right motivation from the beginning. Without money, promises, or incentives, they still join cadet groups out of pure passion.

2. They join for the right reasons. Their interest in the security forces was born at a young age—not out of desperation for a job.

3. They already have basic training. It is common sense to recruit people who already understand the fundamentals.

4. It allows early screening. Experts can identify the strongest, most disciplined, and most resilient candidates before national recruitment begins.

5. It reduces political interference. Early recruitment blocks party protocols and favoritism, ensuring merit-based entry.

6. It ensures recruitment of smart, competent individuals. Many cadets are among the brightest in their schools.

7. It prevents tragedies like the Elwak Stadium stampede. If recruitment pipelines begin early, we will not see 60,000 desperate applicants fighting for space in a 7,000-capacity stadium just to get a job.

In conclusion, the cadets in our high schools and universities are motivated, experienced, disciplined, and ready. Yet the nation overlooks them for political, financial, and self-serving reasons. Ghana cannot build a strong military or national security system on protocol, bribery, favoritism, and desperation. If we want to become a powerful, secure, and respected nation, we must do what strong nations do: Recruit young, recruit early, recruit the motivated, and recruit on merit.